For International Peace Month, we’re looking at significant turning points toward a more peaceful world highlighted by the records of the National Archives. Today’s post comes from Thomas Richardson, an expert archives technician at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, Missouri.

“It isn’t enough to talk about peace. One must believe in it. And it isn’t enough to believe in it. One must work at it.”

–Eleanor Roosevelt

Peace is the goal for every humanitarian in the world. World leaders, activists, and organizations from different nations advocate for the cause of peace and putting an end to conflicts. Whether there’s sporadic violence or a generation of guerrilla warfare, peace becomes the ultimate goal for nations and humanity.

Several U.S. Presidents hosted summits between nations and embarked on programs and initiatives aimed at reducing armed conflict, brokering peace talks, providing humanitarian aid, and advocating for various causes underwriting peace around the world. U.S. Presidents have received the Nobel Peace Prize for their achievements while other leaders have laid the groundwork for national or global institutions that increase international collaboration.

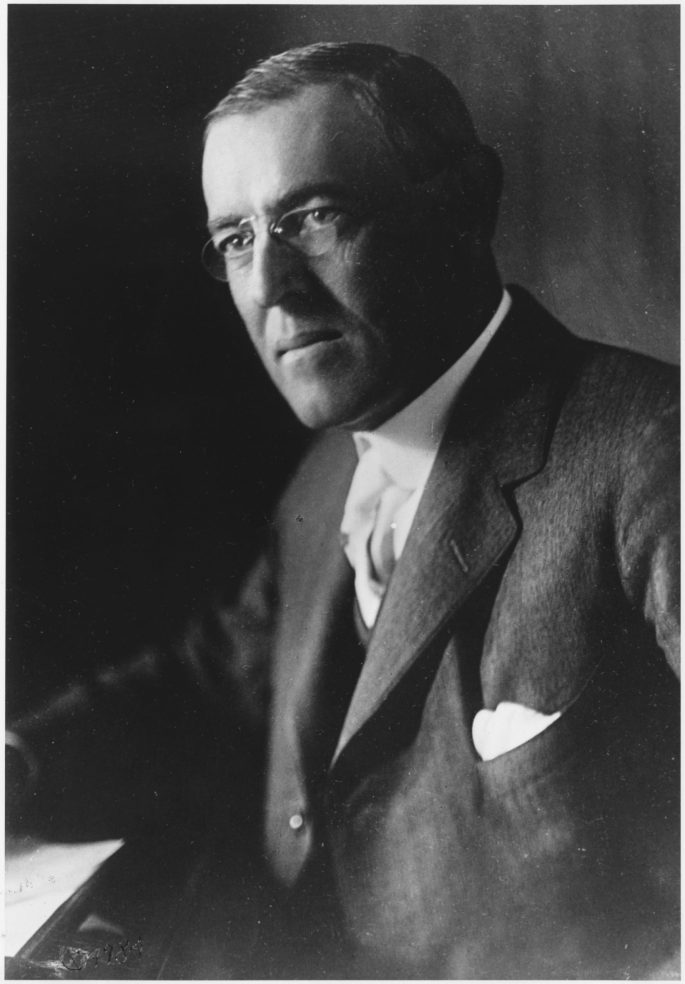

League of Nations, President Woodrow Wilson

In the aftermath of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson believed in the self-determination of nations breaking out from under European colonial rule. In his famous “Fourteen Points” speech, he advocated for the restoration of European sovereignty, the autonomous development of different peoples within nations, and in the final point:

“A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.”

Ideas about an international governing cooperative from multiple nations were debated for decades before the outbreak of World War I. Forty-two founding members signed the Covenant of the League of Nations outlining its goals and policies, and the League of Nations formally came into existence on January 10, 1920. Eventually 58 nations joined the organization; the most notable exception was the United States, when the Senate rejected its membership proposal. For his efforts in establishing the League, President Wilson received the Nobel Peace Prize.

United Nations, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Eleanor Roosevelt

The League of Nations did not last long after its creation. A majority of nations around the world did not join the League, and many of its policies were enforced by those victorious in World War I. Animosities between nations still simmered, making diplomatic solutions from the League almost impossible. Rising dictators like Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini criticized the League for being hypocritical and ineffective, which allowed them to aggressively expand their power.

The idea of a global peacekeeping organization did not die with the League of Nations. President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed in having such an organization again by creating a group that would be guarantors of world peace with a collaboration of armed forces, humanitarian aid programs, and diplomatic processes that also granted veto powers to specific nations.

Steps towards a new group were taken slowly during World War II as the Allied nations outlined their views for a postwar world. President Roosevelt worked tirelessly with Great Britain and the Soviet Union to implement these practices, but on April 12, 1945, Roosevelt passed away and was not able to see his vision become reality.

FDR’s wife Eleanor Roosevelt carried on the necessary work, and in December 1945, she was appointed as the United States’ first delegate to the United Nations General Assembly, where she embarked on some of her greatest humanitarian and work peace initiatives. She was instrumental in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and served as the inaugural Chair of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.

Since its inception, the United Nations has striven to promote peace and alleviate various crises around the world. The Roosevelts, along with so many others, laid the crucial groundwork for this international cooperation.

Atoms for Peace, President Dwight Eisenhower

The Cold War presented new challenges for the cause of world peace. The most threatening that many feared was the potential for nuclear warfare. The atomic bombs that destroyed the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrated how terrifying this new nuclear power could be when weaponized. Many were afraid that the ideological conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union would result in nuclear catastrophe: mutually assured destruction.

In a speech to the United Nations on December 8, 1953, President Eisenhower discussed the importance of the newly adapted atomic powers. The prospect of nuclear power needed to be promoted for peaceful purposes rather than only for warfare. Global standards were required to ensure safety protocols amongst every nation. Atomic development had been developed under strict secrecy, but President Eisenhower brought it to the forefront with the “Atoms for Peace” program.

The program distributed equipment and educational materials to schools and research institutions in order to train people on the merits and safety of harnessing nuclear power. “Atoms for Peace” eventually laid the groundwork for the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Treaty for the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, both of which promote the responsible use of nuclear energy and limit its destructive power.

Peace Corps, John F. Kennedy

Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the fight against communism wasn’t just thought of in terms of nuclear missiles or sabotage. Providing economic aid and development on an international scope could help promote certain values like democracy and liberty. In 1961, one of President Kennedy’s first acts was to create an organization that would employ people to serve overseas as volunteers to assist with economic development. The end result was the U.S. Peace Corps. Ideas like the Peace Corps were shuffled around Washington, DC, for years after World War II. Programs like the Marshall Plan were used as a foundation to see if an organization could achieve the same goal with an international focus.

On March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed Executive Order 10924 establishing the Peace Corps (Congress formalized the Peace Corps on September 22, 1961). Thousands of recent high school and college graduates volunteered within months of the executive order’s signing, and on August 28, 1961, the inaugural group left for their first mission in Africa.

Kennedy’s initial focus was the development of African nations in order to reverse the image of postwar colonialism and imperialism. By 1966, more than 15,000 Peace Corps volunteers were working in over 44 countries. Today, nearly a quarter million people have worked in the Peace Corps in 142 nations, working with local governments on a host of goals and initiatives encouraging development and humanitarian causes.

Reykjavik Summit, President Ronald Reagan

Nuclear weapons had been a dangerous sticking point for both the U.S. and the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War. The buildup of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and other nuclear deterrents were prevalent in both nations. As the 1980s witnessed gradual changes in the relationship between both nations, the subject of nuclear weapons was a major talking point with normalization.

President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative concerned Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, who had advocated for reducing nuclear arms, and in October 1986, the two leaders and their aides met in Reykjavik, Iceland, to discuss the possibility of banning all nuclear weapons in their arsenals.

During the two-day summit, Reagan, Gorbachev, and their aides negotiated and made offers and counter-offers on the prevalence of nuclear weapons, reducing their missile capacity, and dismantling their arsenals all together. The talks stalled on the second day, and ultimately there was no signing of any historic treaty or peace accord in Reykjavik. Despite this setback, there were also discussions on human rights and strategic arms limits.

The following year, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was signed in Washington, DC, which resulted in the dismantling of nearly 3,000 missiles. Historians and legal scholars have often credited the Reykjavik Summit as the breakthrough moment that led to the INF Treaty.

Nobel Peace Prize

U.S. Presidents have had their peace work recognized by the Nobel Prize, awarded to those “those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to Humankind.” Four U.S. Presidents and one Vice President (Al Gore) received this prestigious award:

- Theodore Roosevelt for brokering the Treaty of Portsmouth that ended the Russo-Japanese War

- Woodrow Wilson for his role in creating the League of Nations after World War I

- Jimmy Carter for his lifetime achievement in human rights and promoting economic development

- Al Gore for his contributions to understanding man-made climate change

- Barack Obama for his contributions to international diplomacy

The cause of peace has been the goal for many world leaders, including U.S. Presidents. Whether it’s achieved by banning certain types of armaments or advocating for humanitarian causes, peace between nations is always obtainable. The work of peace is not only done by Presidents but also by diplomats, aid workers, humanitarians, and countless volunteers. Many have brought the cause of peace before the public for years, and it will continue for many years to come.